With most students set to enter public school buildings next month, testing for the coronavirus will be in demand as the Department of Education starts screening for symptoms.

Families turning to the city public hospital system’s free test sites with their children may find language interpretation services in short supply, according to accounts from staff at some of the nearly two dozen locations.

More than 40% of all families in Department of Education-run schools speak a language other than English at home, the city’s Independent Budget Office has found.

Staff at four of the city-run COVID-testing locations in Queens and Manhattan told THE CITY that patients who struggle with English can’t reliably secure interpreters — even though every site run by NYC Health + Hospitals is supposed to offer assistance in more than 200 languages with the help of a phone service.

The language gap affects everything from the accurate recording of patient contact information to the discharge instructions given to those tested, said the workers, who all asked not to be identified.

An employee at a testing site in Woodside, Queens, described having to learn rudimentary Spanish from coworkers and at home in order to better communicate with patients.

Some of the phrases the employee learned: “What’s your name?”; “When’s your birthday?”; “Blow your nose”; “Please don’t move.”

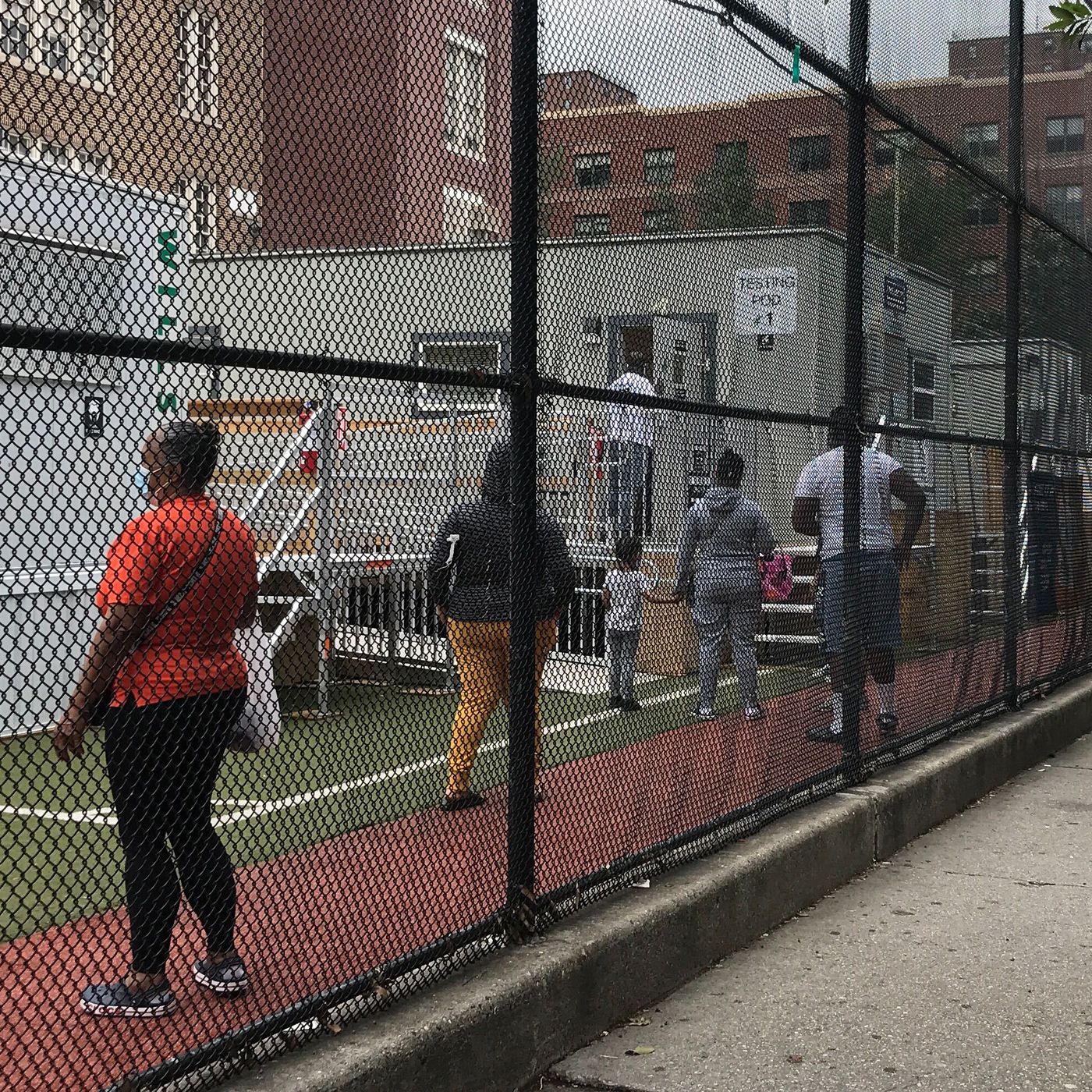

Across the East River, a nurse at a Harlem site had a similar experience. The location, at a public school building, has since closed to make way for students’ expected arrival.

“We were at the mercy of staff that were fluent in Spanish,” they said. “We did not have translator services.”

Rationing Phones

A spokesperson for Health + Hospitals told THE CITY that each of the H+H testing sites in the five boroughs is equipped with at least one designated phone connected to a third-party hotline that offers interpretation services in more than 200 languages.

In practice, say those dealing with patients, the phones don’t deliver.

One employee at a COVID-19 testing location in Woodside said officials sent all but one of its hotline phones to another in Flushing that needed them more.

“I know Flushing was lacking,” the worker said. “They needed it because they don’t have anyone who spoke Korean, whereas more people speak Spanish here.” They said the remaining phone has not been available to them.

A front desk worker at a testing site in Midwood, Brooklyn, said that, while their site has the phones, it can take 30 minutes or longer to reach an interpreter.

The worker told THE CITY that staff at the location advise patients with limited English proficiency to come with a family member who can interpret. That is legal under state law only if translation services are offered and specifically refused by the patient.

Under state and federal law, patients have a right to language assistance services if they do not speak English — and New York hospitals are required to develop language programs and have a program coordinator.

Staff at three sites said they either had no working translator phones or had never seen or had access to one.

A representative from H+H told THE CITY that each site has instructions on how to access the hotline using the translator phones. However, four employees from the three sites who work with patients told THE CITY said they did not know the hotline number and never received any training on how to use the phones.

H+H told THE CITY that employees fluent in a language can talk directly to a patient instead of using a translator phone, and that consent forms and signage are geared toward languages spoken in different neighborhoods.

Wrong Records

The Harlem nurse recalled errors frequently getting made at her site. Because no registration forms or pens were available, staff were expected to register patients by typing in information from their identification documents. (Health and Hospitals asks parents to bring birth certificates or passports for kids.)

If an ID had several names on it, as is common in some cultures, and if the patient was unable to effectively communicate in English, front desk workers sometimes accidentally used an incorrect name to register the patient, the nurse said.

Sometimes, birthdates used to identify patients would also be marked incorrectly. This would cause problems when, later on, a patient would try to access their results and their records would not be found in the system.

“The testing site was taking down the wrong information of the patient,” echoed an employee at the Woodside location. “I always confirm the date of birth and the name prior to testing and sometimes the birthday was way off.”

Sometimes, practitioners would catch these errors and notify the registration unit to get them fixed, employees at both test centers said. At Woodside, however, some patients would have to get retested when they came back for their results that were unavailable due to errors.

Before she swabbed patients, the nurse at the Harlem site said she had to dispose of her protective gloves any time she needed to pull out her phone to use Google Translate.

“You can’t just go in and swab; you have to be able to speak,” she said. “You cannot do patient care without communicating and getting consent.”

H+H allows workers to print out discharge instructions and other “essential documents” in English and 13 other languages.

But patients sometimes got instructions in the wrong language, recalled the nurse at the Harlem site, who said she’d then have to request them to be reprinted. Some patients did not receive verbal discharge instructions at all.

Front desk staff at the Harlem and Washington Heights sites also reported relying on Google Translate because they did not know where the site’s translator phone was, or else would ask bilingual coworkers to assist.

The nurse in Harlem said the staff at her site requested additional translator phones but never received them.

Stephanie Guzman, a spokesperson for H+H, said it was not aware of any formal complaints made about the issue.

“NYC Health + Hospitals has worked to make testing as accessible as possible for every New Yorker across the five boroughs, including non-English speaking patients,” she said in a statement.

“As the City’s public hospital system, NYC Health + Hospitals is proud to provide translation services in over 200 languages and dialects, ensuring that every New Yorker is receiving the COVID guidance they need to stay healthy.”

Schools on Front Lines

School personnel will be directing an untold number of children who develop COVID symptoms to H+H centers and other testing sites by the school system once classes begin — albeit on a strictly voluntary basis.

Children going back to school buildings part-time will have their temperature screened at random on arrival, the city Department of Education vows, and sent home or placed in isolation if their temperature is more than 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

Those who develop any possible COVID symptoms during the school day, according to the plan submitted by DOE to the state, will be isolated until a parent or guardian picks them up.

At that point, the plan states, a “nurse/health professional and/or school staff will advise the family to visit a doctor and get the student tested for COVID-19, and provide the information of the closest testing site, if asked.”

The schools will rely on their own interpretation services for relaying health and safety information, according to a Department of Education spokesperson who promised patient confidentiality would be ensured.

Well before the pandemic, in June 2019, Legal Services NYC filed a lawsuit against DOE alleging that non-English-speaking parents were being denied interpretation services they are entitled to, including in urgent medical situations.

“We know there is more work to do and we will continue to expand our programs to meet the needs of our multilingual students with disabilities,” said DOE spokesperson Danielle Filson at the time.

This year, the U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights reached an agreement with DOE to settle a 2012 complaint from Advocates for Children and New York Lawyers for the Public Interest pressing DOE to improve language access for parents of students receiving special education services.

High-Stakes Testing

At THE CITY’s request, the office of Mayor Bill de Blasio outlined expected steps once a student gets referred for coronavirus testing:

The Test & Trace Corps run by H+H will be notified of any positive results and then reach out to the family by phone, using its own language interpretation services.

That parent, in turn, is responsible for cooperating with Test & Trace to inform a contact tracer what school the child goes to so the school may be alerted.

Students who test negative after developing signs of COVID can return to their school building after being symptom-free for at least 24 hours with clearance from a medical provider — but only if they can provide proof of that result.

Those who do not provide proof or didn’t get tested will have to stay out of the classroom for at least 10 days, in addition to the other requirements.

For those tested at its facilities, H+H advises families to use its call center at 844-NYC-4NYC if a representative does not call with results for a child.

Building Trust

As THE CITY recently reported, language was a barrier to Chinese- and Spanish-speaking residents learning about and using COVID testing services in Sunset Park, Brooklyn — where targeted outreach by Test & Trace has recently yielded more tests taken and more coronavirus infections identified.

As thousands of anxious parents and educators prepare for reentry into school buildings with scaled-down class sizes, masks and social distancing, much will be riding on staff and families quickly identifying potential COVID cases and isolating students safely.

That puts an onus on Health + Hospitals to make sure language is not a barrier to getting tested and getting accurate records on file for each child, say advocates for immigrant families.

“If you’re going to put a system in place, you have to do a certain amount of due diligence when you get an interpreter or contract with a company,” said Ruth Lowenkron, director of the Disability Justice Program at New York Lawyers for the Public Interest.

Carol Horowitz, director of Mount Sinai’s Institute for Health Equity Research, stressed the city’s responsibility in communicating clearly in families’ native languages.

“What they need to do is really have some of these community leaders at the table with them,” Horowitz said, who can offer “rapid feedback” on how testing and tracing in a given community is being “appreciated.”

Otherwise, she noted, people may lose faith in the process and stop seeking out tests, or even a vaccine once one is available.

“We only have so much time we can get it wrong, and then we can’t get it right,” Horowitz said.

The article was published at Many COVID Test-Seekers Lost in Translation at City-Run Testing Sites, Say Staff