With a massive budget shortfall looming, penny-pinchers at the State Board of Education opted to incorporate changes to the high school science curriculum via lower-cost electronic supplements to existing textbooks instead of spending up to $500 million to have new ones printed.

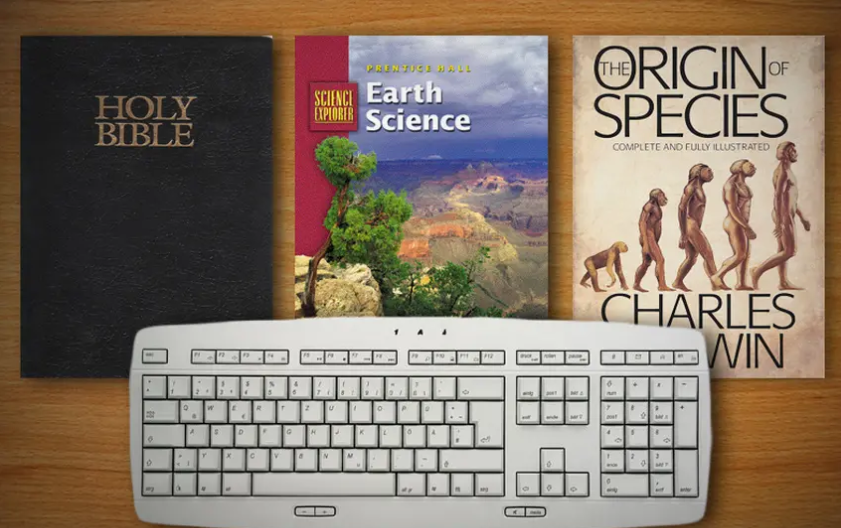

Initially, the move had watchdog groups barking that such supplements, which they insist are not subject to the same rigorous peer review process as ink-on-paper textbooks, provide a ready-made opportunity for mischief: for, say, foes of evolution to introduce the teaching of intelligent design into Texas classrooms — “slipping [it] in the supplementary back door,” in the words of one worried critic.

But the fears may be for naught. Science teachers contend that, notwithstanding concerns of something like a creationist end-run around the curriculum approval process, the problem with electronic supplements is that many schools lack the technical capability to use them — and that while they may save money at the state level, local districts ultimately will see their costs go up.

The SBOE adopted new science standards in 2009 requiring students to learn “all sides” of scientific theories such as evolution and natural selection, but also with updates to biology, physics and chemistry curricula. The board is currently entertaining bids from publishers to provide supplemental materials updating curriculum in current textbooks.

Just what difficulties school districts will face depends on the form the supplements take and what they require from students. That’s in the hands of the publishers: They could provide materials intended just for teachers — like lesson plans to bridge the gaps between existing textbooks and the new standards — or ones aimed at students that require them to complete activities like readings, lab work or quizzes online. The board is set to sign off on the high school supplements in April 2011.

But will anyone be able to access them? According to self-reported data with the Texas Education Agency, one-third of school districts in Texas have five or more students per computer and have no direct internet connectivity in half of their classrooms.

SBOE member Barbara Cargill, R-The Woodlands, a former science teacher, said in an e-mail that what the board has been told is that “schools should at least have computer access either in classrooms or in their libraries.” That sounds good, but in practice, teachers say, resources are often subject to the whim of faulty software and the availability of tech support staff.

“You don’t do labs when you’re scheduled in the computer lab. You do labs when it’s time to do labs,” says Sandra West, a science education specialist at Texas State University. “It’s not effective instruction,” she says, to force teachers to base lessons around when they might have access to the proper technology. “It is wonderful when it works,” she says, “but you don’t see the regular upgrades, the kinds of technical support in public schools” that’s required for it to run smoothly.

The Round Rock Independent School District’s technological infrastructure reflects that of most districts in the state, according to the TEA data. Yet Anita Gordon, who directs the science curriculum there, says that while she thinks her district is “probably in a better position than a lot,” it still doesn’t have the computers and projectors in every classroom “where all of the teachers can have access to them for all of the students.”

Requiring students to access electronic supplements outside of the classroom could also intensify achievement differences between students from poor and wealthy families. Joel Palmer, president of the Science Teachers Association of Texas, says there’s no question that if students must access electronic supplements at home, it will “widen the opportunity gap between students of poverty and students of affluence.”

Demographically, home access to the internet breaks down along racial and socioeconomic lines. U.S. census numbers show that 88 percent of families in the highest income brackets have home broadband access, a percentage that steadily declines in relation to annual family income; in the lowest bracket, just 18 percent have such access. Among ethnic groups, Asians and Anglos have the greatest access, while blacks and Hispanics trail behind by at least 20 percent.

School districts will also have to bear the cost of providing print-outs to students who don’t have computers at home — and, Palmer says, in many cases will be forced to write new, more detailed curricula because teachers won’t be able to rely on up-to-date textbooks.

“I see it as the state pushing off a huge expense from their budget to school districts’ budgets,” Palmer says. In his home district, Mesquite ISD, Palmer says that he will write a new science curriculum from scratch according to the new standards. He said the amount of money districts would have to spend doing this “is going to be huge.”

“My big concern is for small districts that don’t have somebody like me, that don’t have the amount of money to write this kind of curriculum,” he says. “And you’ve got a teacher out there on his own … scrambling right and left to figure out how he’s going to be able to teach these kids the stuff they’re going to be tested on.”

In her e-mail, Cargill explained that board members had considered the possibility that electronic supplements could shift the cost of providing textbooks from the state to the local level. “The Board would never want to burden districts with more costs,” she wrote. “That is why I am hopeful that science textbooks receive full funding as soon possible.”

The Article was originally published on The Techbook Wars