For years, NC Health News has reported on the drug-related deaths, diseases and losses that have resulted from the opioid crisis. Life expectancy in the United States has dropped for two years in a row for the first time in more than 50 years, largely due to overdose deaths among people in the prime of life. While various groups of medical professionals and advocates have tried their best to help people with addiction, the death count continued to rise.

So we wanted to know what it would take to end a drug crisis. With the help of a grant from the Solutions Journalism Network, we were able to send reporter Taylor Knopf to France and Switzerland, two countries that have a lot of experience dealing with opioid addiction. A few decades ago, many European countries saw similar spikes in heroin use and overdoses, along with high rates of HIV and hepatitis C infections. Countries such as France and Switzerland took radical approaches to solve their opioid crises and cut death and infection rates drastically.

“The goal was not to fight drugs anymore. It’s completely ridiculous to fight drugs,” said Jean-Félix Savary, secretary general of the Romand Group of Addiction Studies in Geneva. “It was a big revolution. We don’t try to ask people not to take drugs but take care of problems generated by the situations around people being addicted to drugs.”

The Swiss embraced solutions such as drug consumption rooms and full access to an array of treatment options, including prescription heroin. After that, drug overdose deaths dropped by 64 percent, HIV infections dropped by 84 percent and home thefts dropped by 98 percent.

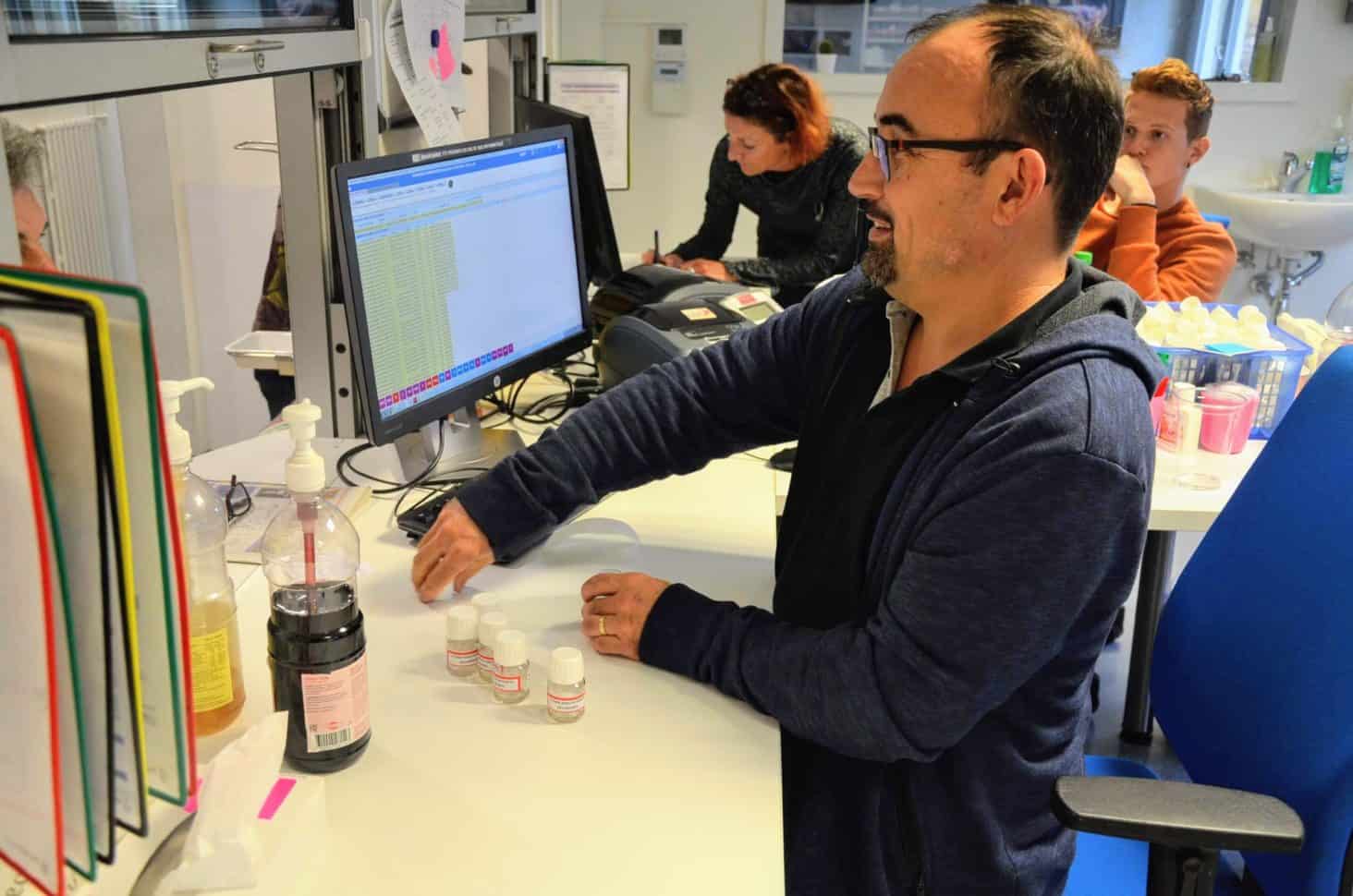

With the help of interpreters, we talked to addiction psychiatrists, doctors, nurses, social workers, educators, policy influencers, chemists and drug users.

In France, the harm reduction strategies are not quite as cutting edge as in Switzerland. Instead the French work to support drug users through full-service harm reduction centers that offer wrap-around services, such as clean needles, medication-assisted treatment, counseling, medical treatment, hot showers, laundry machines, life skills classes, and places to sleep.

Given the readership and comments on these stories, it appears people are ready to entertain new approaches to addressing the nation’s opioid crisis.

North Carolina prepares to transform the Medicaid system

It was a roller coaster of in 2019 for what was billed as the most dramatic transformation to the state’s health care landscape in decades – the planned switchover to managed care for the state’s Medicaid program.

Medicaid is the public health care program that, at its core, provides healthcare for 2.1 million poor children, seniors and disabled persons in North Carolina, meaning one in every five North Carolinians depends on Medicaid for care. As part of former Pres. Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act, many states have opted to extend Medicaid coverage to low-income, single adults, with the federal government ponying up most of the funds for that coverage.

North Carolina has not expanded Medicaid to cover between 365,000 and half a million adults largely now without health care coverage, the issues have been the root cause of this year’s unprecedented standoff over the state budget between Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat, and Republican state legislative leaders. (In short, Cooper is for Medicaid expansion; Republican state lawmakers are not.)

Caught in the crosshairs of this fight over the state budgets and Medicaid expansion is a years-long planned switch to move the state’s existing Medicaid program, which costs about $14 billion in state and federal funding. The program currently has the state essentially cutting a check for every flu shot, hospital stay and therapy visit beneficiaries need.

The switch would hand off the bulk of the Medicaid rolls to managed care companies, paid with a per-person rate, to handle people’s health care needs – $30 billion worth of state money in contracts to five managed care groups over five years. Medicaid transformation, the phrase that the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services has adopted, also will put in place a series of ambitious changes addressing what are called social determinants of health, life experiences such as homelessness, food insecurity, and exposure to violence that undermine people’s quality of health.

The state had planned to see part of the state rollover to this new system by November and then have the whole state on board by this February. But DHHS Sec. Mandy Cohen pulled the plug on the planned switch, citing uncertainty from the lack of a state budget.

“To date, we have been able to use other Medicaid funds to continue this work but at some point we need the new budget in order to keep going and so as of now, we have to suspend,” DHHS Sec. Mandy Cohen told N.C. Health News in November.

So, for now, there’s no set plan or date as to when the state will get back on track with moving Medicaid to managed care.

“We do not want to set a date until we have absolute certainty about the budget,” Dave Richard, the N.C. DHHS deputy secretary in charge of Medicaid told NC Health News. With the other two delays “people were geared up to do that work, they were prepared to do that work, and then we changed it and that just creates lots of chaos and conflict with folks.”

Medication-assisted treatment has the potential to tame the opioid crisis, if it’s available

In July, we reported that North Carolina used $54 million in federal grant funding to help more than 12,000 people receive treatment for substance use disorders. But according to data from the state, most of the people who benefited from these grants were disproportionately white.

Of roughly 10,000 participants who entered treatment in the last two years, more than 9,000, or 88 percent, were white, about 7.5 percent were African American, and fewer than 1 percent were American Indian. Yet opioid death rates are far higher among North Carolina’s American Indians, according to the North Carolina Medical Journal.

Racial bias in access to substance use disorders treatment is a persistent problem in North Carolina and across the nation, and many people of color don’t have the same access to medications such as Suboxone and methadone as their white counterparts. These disparities are particularly important because the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration considers medication-assisted treatment or MAT, to be the gold standard in treating addiction, along with counseling.

Access to such medications isn’t only hampered along racial lines. Also in July, we reported that 41 of North Carolina’s 100 counties had few providers who could prescribe these medications, coupled with higher rates of opioid-related deaths.

We’ve also reported on efforts to increase access to medication-assisted treatment in one North Carolina county jail and statewide efforts and a program to increase the number of providers who can prescribe these medications across the state and improve patient access to these services.

APRNs, other practitioners, seek more practice autonomy

North Carolina continues to have wide disparities in where health care practitioners see patients. According to data from the Sheps Center for Health Services Research at UNC Chapel Hill, in more than two dozen counties, there are only dentist or none, in 28 counties there are no obstetricians or gynecologists to provide care for women or deliver their babies and in 28 counties there are no psychiatrists, 35 lack psychologists.

That’s on top of the low number of primary care practitioners in the state. North Carolina has 132 family medicine doctors per 100,000 residents, compared to neighboring Virginia with 144 per 100,000 or even West Virginia with 168 family docs per 100,000 residents.

Family physicians were the most in-demand specialty for the 13th year in a row, earning average national salaries of $239,000, according to physician search firm Merritt Hawkins’ annual report of clinician recruitment.

That’s part of the reason why so-called “mid-level” practitioners feel like there is a case to be made for removing restrictions on their scope of practice, the set of laws and rules that dictate what each type of health care licensee can do. These providers point to decades of research that indicates their care is safe and effective and point to positive outcomes in dozens of other states with more liberal practice guidelines.

Earlier this year, nurses came to the legislature to press their case for an expanded scope of practice. Nurse midwives, nurse practitioners and certified registered nurse anesthetists have hired lobbyists, made strategic political donations, and made a more aggressive push for legislative action to give them increased practice autonomy.

In February, identical bills were filed in both the House and Senate to change nursing practice and bring the state in line with 22 other states and the District of Columbia which allow these advanced practice nurses more autonomy.

“Most of the counties I represent you will find that from 5 p.m. on Friday to 9 a.m. on Monday your only option for health care is the emergency room,” said Sen Ralph Hise (R-Spruce Pine), who represents six rural mountain counties as he introduced the Senate version of the bill.

Hise cited research showing that APRNs are more likely than physicians to practice in a rural area and North Carolina data showing that nurses who train locally are more likely to practice in a rural area than physicians.

But the bills didn’t move far in the legislature.

In the world of dental care, hygienists seemed to be making more progress in gaining the ability to practice without a dentist in the same building.

Hygienists in North Carolina have pressed for years to be able to clean teeth, check gum health, apply sealants and take x-rays without needing a dentist nearby.

A proposed rule change endorsed in 2019 by the N.C. Board of Dental Examiners cleared many hurdles in 2019 and garnered numerous favorable comments at public hearings, as well as in written comments.

The notion, supporters explain, is to take the step forward with a goal of moving toward a giant leap in the next decade toward an even broader scope of practice for hygienists.

Allowance hike for NC adult care home residents advanced, but stalled along with budget

A proposed increase in the spending money available to tax-financed residents of North Carolina assisted living centers got a strong push from legislators and advocates in 2019, and nearly passed into law.

Called the personal needs allowance, the stipend for residents on Medicaid has been stalled since 2003 at $46 a month. This paltry amount is intended to cover items such as toothpaste and shampoo, transportation, snacks, prescription drugs and even medical copays.

Budget writers from both parties in the state House included an increase to $70 a month, while GOP legislators in the state Senate crafted a hike to $58 month in the current fiscal year, then to $70 in 2019-2021.

But this provision was vetoed by Gov. Roy Cooper, along with the rest of the budget, because the legislature failed to include Medicaid expansion, a policy which would add about 500,000 people to the publicly funded program. Despite months of effort, Republicans have not succeeded in overturning the governor’s veto of the budget.

The legislature has passed and Cooper has signed a series of mini-budgets to fund many state services, but none of the funding has included revised levels for health and human services. That means that funding for the personal needs allowance has remained at the long-unchanged rates.

During budget preparations, North Carolina Health News and other outlets reported on the downside of a low-end allowance for residents trying to maintain quality of life.

Reporter Thomas Goldsmith heard from Judy Vines Hendrickson, a resident of Sharpsburg, who told NC Health News that the rate has affected both her adult son, who has mental illness and lives in a group home, and her late sister, who traded sex for spending money while a resident of an assisted living center in eastern North Carolina.

“I really wish that the people making these decisions would have a panel of people like me come up there and talk to them,” Hendrickson said.

The future of hemp debated in North Carolina

Hemp, a newly legalized crop, took center stage during legislative debates on the 2019 Farm Act this year. The bill pitted farmers against law enforcement, two groups with a lot of pull at the North Carolina General Assembly.

NC Sheriffs and prosecutors filled committee rooms asking lawmakers to classify raw hemp flower as marijuana, a controlled substance.

Hemp and marijuana look and smell exactly the same; however, one has been grown for its psychoactive properties while the other has been bred to not induce a mind-altering high. Law enforcement argued that raw hemp should be illegal because they could not tell the difference between the two and would not be able to enforce the state’s current marijuana laws.

“The state crime lab does not have the testing equipment to test a green leafy substance to tell if it’s smokable hemp or to tell if it’s marijuana,” said Eddie Caldwell, general counsel of the NC Sheriffs’ Association. “And without the ability to get a test from the state crime lab, it puts the district attorneys in an impossible situation trying to try the case in court.”

Meanwhile, farmers who are suffering from plummeting commodity prices and hurricane losses say they are finally reaping some real profits from growing hemp. They begged lawmakers to leave the crop alone and allow them to continue farming it.

“Last year we ventured out into hemp and some other crops trying to diversify our farm, but the hemp has been a blessing for us,” said Bryan Atkins, a 27-year-old farmer from Moore County.

“We want a future in agriculture,” he said. “With commodity prices and all, we cannot make a sustainable living off of soybeans and corn, especially since our tobacco is gone. The hemp has given us the opportunity to explore other options.”

Lawmakers engaged in heated debate over whether or not to impose restrictions on the hemp flower, with powerful legislative leaders backing each argument. Ultimately, the bill was withdrawn and has not been passed. Lawmakers could take it back up when they reconvene in Raleigh in January.

This article was originally published on What stories grabbed you in 2019? NC Health News most-read stories of the year